On this page

Early Days

Long before the first European inhabitants arrived at the site of what was to become one of Canada's oldest cities, the Mi'kmaq people set up summer camps for fishing and hunting on the shores of the harbour they called Chebookt.

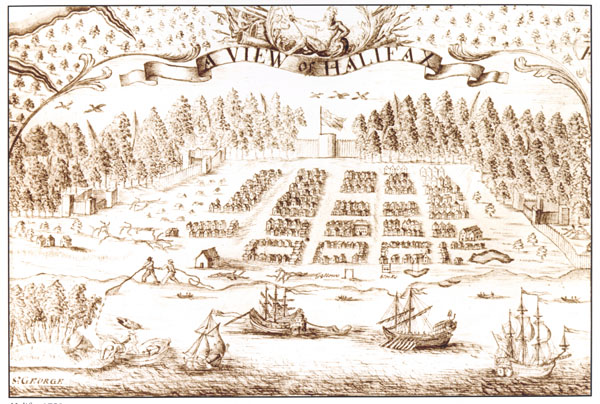

The area around the harbour became known as Chebucto. The British first became interested in creating a settlement at Chebucto to counter the French presence at Fort Louisbourg on Île-Royale (now Cape Breton Island). The British settlement plan involved the recruitment of around 2,500 people, mainly from England. Edward Cornwallis, a 36- or 37-year-old army officer and former member of Parliament, was appointed Captain General and Governor-in-Chief. He was in charge of settlement operations.

On June 21, 1749, the Sphinx arrived in the harbour and the following day Cornwallis wrote to the Duke of Bedford, reporting:

« ... the coasts are as rich as ever they have been represented. We caught fish every day since we came within fifty leagues of the coast, the harbour itself is full of fish of all kinds; all the officers agree the harbour is the finest they have ever seen. The country is one continual wood, no clear spot to be seen or heard of. I have been ashore in several places -- the underwood is only young trees so that with difficulty one might walk through any of them; D'Anville's fleet have only cut wood for present use, but cleared no ground, they encamped their men upon the beach.

» - Payzant, p. 15

A total of 13 transports arrived over the next weeks, bringing men, women and children. The crossing had been a good one with few deaths and upon arrival the settlers were sheltered in tents along the north shore of George's Island.

Cornwallis's first task was to lay out the town grid. McAlpine's Nova Scotia Directory for 1869-70 describes the process:

In the month of July, Mr. Bruce, a civil engineer, and Mr. Morris, a surveyor, were ordered to lay out the town, which was surveyed and the plan completed by the 14th September. The town was laid out in squares or blocks, of 320 by 120 feet -- the streets being from 55 to 60 feet wide. The width of Granville Street is but 55 feet. Each block contained sixteen town lots, 40 feet front and 60 feet deep. The whole was divided into five divisions or wards. The settlers drew for the lots, and the names and number were entered on a register kept for that purpose, still in existence, and known as the allotment books.

- McAlpine's Nova Scotia Directory, 1869-70, p. 153-4

The selected location, close to the ocean, provided sheltered, deep-water anchorage and could be easily defended from attack by either land or sea. Before autumn, about eight hectares had been cleared for the town that Cornwallis had decided to name Halifax, after George Dunk, Earl of Halifax. The town was framed by five log forts, joined by a log palisade. By late autumn, around 300 houses had been completed at the foot of a large hill on the west shore of the harbour.

The first settlers were joined over the next couple of years by several hundred Protestant immigrants from Germany. In the mid-1750s most of these new arrivals moved to Lunenburg on the province's south shore, although some remained and settled down to farm at what became known as Dutch Village (from the German Deutsch, meaning "German"), on Halifax's western boundary.

The next group of people to come to Halifax, lured by government money, was an influx of Americans, mostly businessmen and professionals. Along with these new immigrants came Black men, women and children, many of whom were servants. Others were slaves. Slavery was present in Nova Scotia until the 1790s.

Though Cornwallis met with the Mi'kmaq and offered them small gifts, he at no time entered into negotiations for the land that became Halifax. Frustrated by the settlement's numerous problems and weakened by ill health, Cornwallis resigned as Nova Scotia's governor and returned to England in 1752.

Cornwallis's replacement, Peregrine Hopson, during his year as governor, sought peace with the Mi'kmaq but could not stop the hostilities between Britain and France.

When Charles Lawrence took over, it was he who decided the fate of the Acadians in Nova Scotia. Halifax was to play a major role in the tragic saga of the Acadian expulsion. Thousands of Acadians were housed on Georges Island while awaiting deportation.

The continued hostilities between Britain and France provided the impetus for increasing funds from Britain to fortify Halifax, now considered an important military base. His Majesty's Naval Yard, with numerous buildings and wharves, was built on the harbour's shores beginning in 1758. The top of Citadel Hill was redesigned with new wooden walls and trenches to defend the town from overland attack. Most of the work at this time was related to the garrison, with military personnel outnumbering civilians six to one. As early as 1760, demobilization drove people to move away and the population of Halifax was halved.

Halifax began to rely more on trade with Boston and other New England centres. Life became harsher for the town's poor, many becoming increasingly dependent on relief for survival.

The coming of the American Revolution provided Halifax merchants with money-making opportunities. So close to the fighting and with a wonderful harbour and naval yard facilities, Halifax became the military base for the Royal Navy. By late 1775, the town was bustling with imperial ships, men and munitions, and the merchants were making huge profits.

After the war there was an influx of American Loyalist refugees, many of whom were poor and discouraged by the life they now faced. Insufficient housing, poor diets and rampant crime added to the misery. Among these new immigrants were African-American Loyalists, many of whom had won their freedom by fighting for the British. While waiting for the promised grants of land, many remained in Halifax but over time gradually moved to small land grants in rural districts. Many Black settlers left Nova Scotia in 1792 for Sierra Leone, in search of a better life.

Growing Pains

As before, in times of peace, Halifax was struggling to get by. With the Napoleonic Wars in 1793, Halifax once again became a fortress and naval base, though the fortifications had been allowed to fall into ruin.

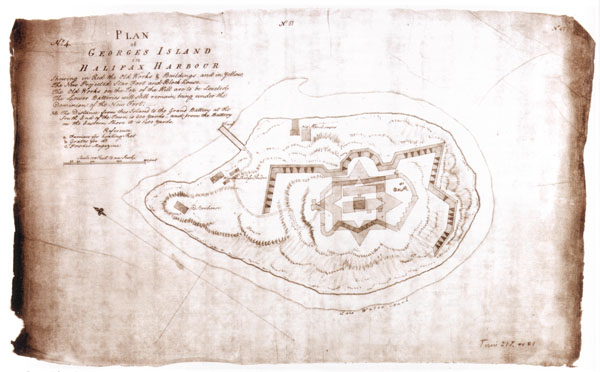

In 1794, 27-year-old Prince Edward (father of Queen Victoria) came to Halifax, where he would remain for six years. Edward launched a series of harbour refortifications. The defences at the top of Citadel Hill were again replaced with new wooden walls and trenches. Edward designed a star-shaped fort, with five stone towers built at strategic points, along with a communications system which could relay messages between fortifications using flags, pennants, and black balls by day and lanterns at night. Halifax's economy picked up. Prince Edward also built Fort Charlotte on Georges Island, named for his mother; and a wooden mansion on the shores of Bedford Basin, called the Prince's Lodge, that contained a music pavilion, garden pathways, ponds and Chinese temples. Edward's final construction was a garrison that became known as the Old Town Clock, standing on the eastern slopes of Citadel Hill.

The 1790s saw a growth of trade with the British West Indies. The sailors on board these vessels suffered hardships such as shipwrecks and "yellow jack," a tropical fever. With the Napoleonic Wars also came increased danger. Sailors could be carried off by press gangs to serve in the Royal Navy, only to be taken prisoner aboard French vessels and face imprisionment in the Caribbean.

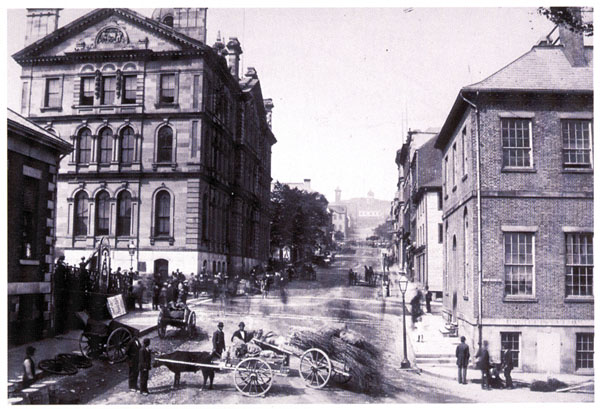

By 1810, Halifax was the region's foremost commercial port. Halifax now handled European manufactured goods, American foodstuffs, Caribbean produce and colonial fish and timber. Irish Roman Catholic labourers had become the most common immigrant to Halifax, most arriving in the 1830s.

In 1812, Halifax found itself at war with its New England neighbours. Residents feared that Halifax was vulnerable to attack and could also be cut off from the trade it enjoyed and the American food imports it depended on. However, American merchants continued to come to Halifax to exchange goods for European manufactured goods and Caribbean produce.

Province House, housing the legislature and Supreme Court, opened in 1819. Around the same time, Alexander Keith, a Scottish immigrant who had arrived at the end of the War of 1812, opened his brewing business. His India Pale Ale became a staple for those stationed at or working on the harbor fortifications.

In 1828, engineers began to build a star-shaped series of walls and trenches. This new fortress on Citadel Hill, named Fort George in honour of the King, was not completed until the 1850s. Modernizations to Fort Charlotte on Georges Island were completed in 1873.

As Halifax grew, there was a call for change in the town's management, a change that would require Halifax's incorporation as a city. Prosperity among the master craftsmen and shopkeepers allowed for the acquisition of real estate, education and leisure time. This segment of the population also began to take a greater interest in civic affairs. There was a move to improve the quality of life in Halifax.

Coming of Age

Halifax was incorporated as a city in 1841. Before the 1840s, a few sewers had been built, though most waste was dumped into cesspools. A few public wells had been dug, but these often went dry in the summer. Most of the residents relied on backyard wells for their water. Typhoid remained a problem and source of death. The Halifax Water Company first piped water into the city in September 1848.

Water for firefighting was very important in a city with so many wooden buildings. In the early days of firefighting, when a fire broke out, someone would rush to the firehouse and sound the alarm. Volunteers then arrived to form a bucket brigade to the nearest well or pump, or even the harbour. The firefighting brigade was composed of volunteer members until the mid-1890s, when part-time firefighters were employed. There were no full-time firefighters until 1918. Though it escaped the great fires of other Canadian cities, Halifax did have its share of devastating blazes. After a serious fire in 1861, the city bought steam-powered engines and purchased the Halifax Water Company.

In 1846, Halifax had twelve constables on staff during the day, while twelve volunteers patrolled the streets at night calling out the hours. These two services merged in 1864, creating a more modern law enforcement agency. Thirty constables, under six sergeants, were given their orders by a magistrate until 1870, when the mayor regained authority over the police.

For many years, Halifax was condensed into a small enough area for its residents to travel most places by foot, horse or sedan chair. Ferries carried passengers between Halifax and Dartmouth. Sailing ships and steamers were in use for people whose destinations were further afield. Halifax's first steam-powered vessel, the Sir Charles Ogle, and another steamer, the Boxer, added greatly to Halifax's public transport in the 1830s. Halifax resident Samuel Cunard won the contract for a scheduled steam-packet service from Liverpool to Boston, via Halifax. On June 1, 1840, the first of Cunard's vessels, the Unicorn, powered by a coal-fuelled engine, arrived in Halifax harbour. As the city grew and spread, horse-drawn streetcars were introduced, running from the south end of Halifax to the railway depot by 1866 - much to the chagrin of the cabmen and operators of omnibuses. Electric streetcars were introduced in 1896 by the Halifax Electric Tramway Company.

While it was widely felt that development depended on construction of a railway, paying for it was a less popular notion throughout the 1850s and 1860s. The short railway lines built during this time period had resulted in debt. The promise of an intercolonial railway, funded by a source outside city council, aided the acceptance of Confederation.

In 1843, gas lamps were installed on streets in the central part of the city, replacing the seal or whale oil lamps. Electric street lights appeared in 1886, and by 1890 Halifax was the first city in North America to be lighted completely by electricity. The Dominion Telegraph Company operated a telephone service for 25 subscribers in 1879. Bell Telephone Company took over and by 1888, Halifax had 400 telephones.

Beautification of the city progressed with the development of the Horticultural Gardens in the late 1830s and early 1840s. The Gardens were open to those who could pay the entrance fee. They became known as the Public Gardens when they became city-owned in 1874.

Many Halifax women worked to improve life for the city's inhabitants. Isabella Brimney Cogswell, daughter of financier Henry H. Cogswell, used her inheritance to promote many charities and co-founded the Protestant Orphans' Asylum. Another contributing member of society was Anna Leonowens, who helped form the School of Art and Design in 1887. Leonowens was the teacher whose story was made famous in Rodgers and Hammerstein's The King and I.

Industrialization came to Halifax in the 1870s. The Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company operated from 1883 until 1891 when it was taken over by Dominion Cotton Mills Company of Montréal (later Dominion Textiles.) At the time, the cotton factory was Halifax's second-largest industry. Small factories, part of the Halifax landscape since the mid 1800s, gave way to larger enterprises, manufacturing such goods as candy, boots, rope and steam engines. William C. Moir was a military contractor who used his profits to support a factory that produced bread, biscuits and candy; milled flour; and made boxes. Starr Manufacturing, with its plant in Dartmouth and offices in Halifax, manufactured the patented Acme ice skate, as well as iron goods such as nails and bridges. Halifax built Canada's first covered skating rink in 1867.

Halifax's development has been one of ebb and flow, affected by times of war and peace. Through it all, Halifax retained its reputation as a national port. Even in lean times, with conditions of poverty, overcrowding and disease, Halifax managed to welcome newcomers to Canada, providing immigrants with support as they began a new life.

Image Gallery

[ig]

Governor Edward Cornwallis (1713-1776), born in London, England

Halifax, 1750

View of the Naval Yard, Halifax, 1796

Black woodcutter sawing a log while wearing a "liberty cap", a symbol of having attained freedom from slavery

Prince's Lodge, 1839

The Old Town Clock, Halifax; at least one of its four faces is visible from most points in Halifax's old downtown, Georges Island and the harbour

Prince Edward's plan for the new fort on Georges Island in Halifax harbour, 1794

Government House, completed in 1808, is a reflection of the prosperity of the early 1800s. Its high construction costs caused controversy at the time

McAlpine's Halifax City Directory for 1875-76, p. 3

Street vendors, Halifax, 1899

References

- Fingard, Judith. The Dark Side of Life in Victorian Halifax. Porters Lake, N.S.: Pottersfield Press, 1989.

- Fingard, Judith, Janet Guildford, and David A. Sutherland. Halifax: The First 250 Years. Halifax: Formac Publishing, 1999.

- "Halifax" and "Halifax Citadel." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1985, 3 vol.

- Halifax and Its People, 1749-1999: Images from Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management. Halifax: Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management and Nimbus Publishing, 1999.

- Marshall, Dianne. Georges Island: The Keep of Halifax Harbour. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2003.

- Payzant, Joan M. Halifax: Cornerstone of Canada. [Halifax]: Windsor Publications, 1985.

- Raddall, Thomas H. Halifax: Warden of the North. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 1993.

- Shannon, Kate Winnifred. A Victorian Lady's Album: Kate Shannon's Halifax and Boston Diary of 1892. Halifax: Formac, 1994.

- Sutherland, David A. Halifax, 1749-1849: Garrison into Metropolis. [Ottawa]: National Museum of Man, National Museums of Canada, [1979?]. (Canada's visual history; vol. 37).

- Watts, Heather, and Michèle Raymond. Halifax's Northwest Arm. Halifax: Formac Publishing, 2003.

- Withrow, Alfreda. One City: Many Communities. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 1999.